he turkey is one of the most quintessential American foods, through its association with Thanksgiving and its reputation as one of the bounteous foods that Europeans encountered in the New World. But our modern feast actually bears little resemblance to the 1621 Pilgrim harvest celebration commonly known as the “first Thanksgiving,” or the Puritan tradition of observing holy days of thanksgiving.

to the 1621 Pilgrim harvest celebration commonly known as the “first Thanksgiving,” or the Puritan tradition of observing holy days of thanksgiving.

Days of thanksgiving were common in many colonial American communities throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, typically declared by ministers or governors in response to specific occasions, such as a military victory, a plentiful harvest, or beneficial rainfall, but no specific Thanksgiving Day was celebrated on a yearly basis. For both the Pilgrims and Puritans, days of fasting and thanksgiving, like the Sabbath, were serious occasions marked by long sermons, prayer, and time off from work and play.

Eventually the idea of feasting as part of a day of thanksgiving evolved as an alternative to the fall harvest festivals that were part of the British culture, particularly in the New England area where many people missed these traditions from their homeland. Turkeys (along with other food and drink) were included in these celebrations. The gathering of extended family as part of these events became more significant during the late eighteenth century, and the foods associated with the New World, such as turkey, pumpkin, sweet potatoes, and cranberries were increasingly integrated. Thanksgiving as we now know it began to emerge.

Eventually the idea of feasting as part of a day of thanksgiving evolved as an alternative to the fall harvest festivals that were part of the British culture, particularly in the New England area where many people missed these traditions from their homeland. Turkeys (along with other food and drink) were included in these celebrations. The gathering of extended family as part of these events became more significant during the late eighteenth century, and the foods associated with the New World, such as turkey, pumpkin, sweet potatoes, and cranberries were increasingly integrated. Thanksgiving as we now know it began to emerge.

The relationship between Pilgrims and Thanksgiving can be linked back to Rev. Alexander Young’s Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers, published in 1841. In the book, Young included a copy of a letter dated December 11, 1621 from Edward Winslow, one of the Plymouth colony leaders, describing a three-day feast enjoyed by the colonists and a large group of Native American guests held after the crops were harvested. Winslow did not specifically mention wild turkey in his letter—only that four men went hunting and brought back large amounts of fowl, which could have been any type of birds, such as ducks, geese, or even swans. On his own accord, Reverend Young added a footnote stating, “This was the first Thanksgiving, the harvest festival of New England. On this occasion they no doubt feasted on the wild turkey as well as venison.” In order to substantiate his turkey reference, Young cited Governor William Bradford’s 1650 manuscript, “Of Plymouth Plantation,” which states that in the fall of 1621 “a great store of wild turkeys” was available at the colony. So while it was a real possibility that turkey was one of the birds served at this feast, it was essentially Young’s statement that secured a place for turkey on the Thanksgiving menu.

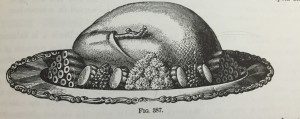

By the 1850s, almost every state and territory celebrated Thanksgiving, but it didn’t become a national holiday until President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation in 1863, the result of a seventeen-year campaign by Godey’s Lady’s Book editor Sarah Josepha Hale. She was able to convince President Lincoln that a national Thanksgiving might help heal the nation after the devastating Civil War. Soon after, with the Victorian era and all its opulence, Thanksgiving dinner became the one of the most carefully planned menus of the year for most families, with roast turkey the main feature.

By the 1850s, almost every state and territory celebrated Thanksgiving, but it didn’t become a national holiday until President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation in 1863, the result of a seventeen-year campaign by Godey’s Lady’s Book editor Sarah Josepha Hale. She was able to convince President Lincoln that a national Thanksgiving might help heal the nation after the devastating Civil War. Soon after, with the Victorian era and all its opulence, Thanksgiving dinner became the one of the most carefully planned menus of the year for most families, with roast turkey the main feature.

Preparations for this highly anticipated meal were done well in advance. Homes were colorfully decorated with seasonal autumn leaves, chrysanthemums, asters, palms, ferns, dried grasses and grains. Mince pies and plum pudding were baked at least a week or two ahead. The dinner table was set with pretty china dishes, crystal glasses and silver flatware. Tapered candles illuminated the dining room with a soft, mellow glow, and fireplaces blazed with a cozy light. Children had their own attractively set table adored with brightly colored flowers, fruit and candy.

Oyster soup or consommé started the meal, and then came the roast turkey along with boiled onions, squash, mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce or jelly, pickles, catsup, celery and apple sauce. Sherbet was served after the turkey to cleanse the palate and make room for chicken pie or another rich savory dish such as quail or roast duck. Desserts included treats such as pumpkin pie, sponge cake, cranberry tart, Thanksgiving (plum) pudding, fruits, nuts and ice cream. After enjoying all these delicious foods, guests would typically top off this festive dinner by retiring to the parlor to sip coffee and liquors.

(Sources: Excerpt from The Thousand Dollar Dinner (Westholme, 2105) by Becky Diamond; Table Talk Magazine, Volume 14, Nov 1899)

Don’t miss Becky Diamond’s illustrated talk about the 1851 culinary duel between Delmonico’s, NYC, and Parkinson’s, Philadelphia. Click here for tickets https://ebenezermaxwellmansion.org/lectures/